In the early 1920s a major fire broke out at Liverpool docks. Four brave dockworkers managed to get the blaze under control, saving the docks, the ships and a large part of the city. Their reward? Just £17.

The public was outraged. And the Order of Industrial Heroism was born. Launched in 1923 by the TUC, the Order of Industrial Heroism was nicknamed ‘the Workers’ VC’. While the Victoria Cross rewards bravery on the battlefield, the Order of Industrial Heroism honoured bravery in the workplace. Here are the stories of six people of the 440 people who received the honour.

“Engine running away! Engine running away!”

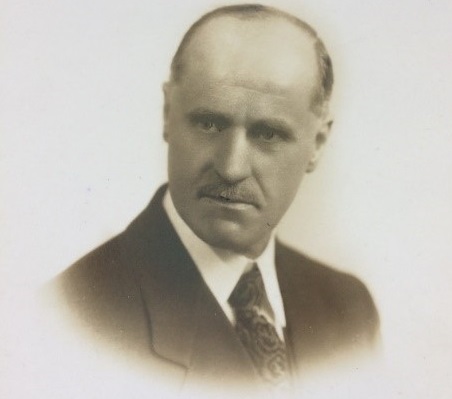

Mr A H Sutton, engine driver, Sheffield, July 1924

When A H Sutton spotted a runaway train as it travelled at 30 miles per hour around the Vickers Engineering Works he leapt onto his own train, ran it on the tracks in front of the runaway and varied his speed until it caught him up. Just as the two trains’ buffers touched, Mr Sutton applied his brakes and bought both trains to a standstill. His courage and skill probably saved many co-workers from serious injury – or worse. But when he received his Industrial Heroism Award at the Coliseum Picture Palace, Mr Sutton described the incident as “a little matter”.

Into the freezing water

Alfred Flynn, Dockworker, Preston, November 1924

On a dark November afternoon in 1924, dockworkers Henry White, 33, and 16-year-old Alfred Flynn were unloading timber when Henry’s foot slipped. He plunged into the freezing water between a ship and the quay wall, hitting his head on the way down. Alfred dived in and held Harry up until a rope was thrown down. MP Tom Shaw gave Alfred his award at Preston Public Hall, saying it was, “time the Labour movement recognised the services rendered every day by working men to their fellow men, in docks, factories, and mills, and the institution of this Order has filled a long-felt need”.

“I thought it was my duty.”

George Jones, miner, Swansea, April 1925

In November 1924, a sudden surge of water flooded the Killan Colliery. Two men were killed instantly and 11 were trapped inside. Eight men survived by breathing from an air pocket while their friends above ground – George Jones among them – made frantic attempts to get them out. They were rescued after 50 hours underground. Such was the scale of the tragedy at Killan that it’s unsurprising that George kept his speech low-key when he accepted his award in Swansea in April 1925: “It was God’s pleasure that I should save men, and I thought it my duty, as every other British worker would have done.”

Into a scalding vat

Robert Pearson, Labourer, Stockport, October 1925

At the bleach works in Stockport where he worked, Robert Pearson heard screaming. Two boys, Arthur Bowden and William Stothert, had been working in a vat when there was a sudden inrush of scalding liquid and steam. Arthur managed to get out through a manhole but William couldn’t get a grip it with his burning hand. Robert, 29 with a young son at home, jumped down and hoisted William out. Robert was dragged out of the vat barely conscious, his feet badly scalded. Both boys died of their injuries but Robert’s actions were recognised with a medal. Robert lived until 1973.

Saving Amy from the train

Anthony Rivers, Railway porter, Stourbridge, June 1955

In October 1954, railway porter Anthony Rivers saw 66-year-old Amy Rowlands struggling at the level crossing where he was on duty. He realised her foot was stuck between two lines. As a train approached Anthony frantically tried to pull Amy free, trying to cut her shoe loose but the train was too close. The only way to save Amy’s life was to sacrifice her foot. Anthony held her by the shoulders as far from the line as he could and shielded her with his body. The train severed Amy’s right leg below the knee. Anthony was also injured but he managed to drag himself to the platform to get help.

Fire in the fields

Ruth Stanaway, Potato riddler, Gainsborough, May 1962

Ruth Stanaway was the first and last woman to be honoured for bravery at work. Ruth, 32, sieved and sorted potatoes for a living. In November 1961, Ruth and her fellow workers were huddling around a fire to keep warm as they ate their lunch. Despite warnings, one woman poured a can of oil onto the fire. A violent explosion enveloped 19-year-old Margaret Palmer. Ruth grabbed some potato sacks and wrapped them around the teenager, gradually putting out her blazing clothes. Doctors said Margaret would have died if Ruth hadn’t reacted so quickly. Ruth spent ten days in hospital being treated for burns on her face and hands.