Seven interesting things you should know about the small but mighty William Cuffay, who fought tirelessly for workers’ rights in the 1800s

-

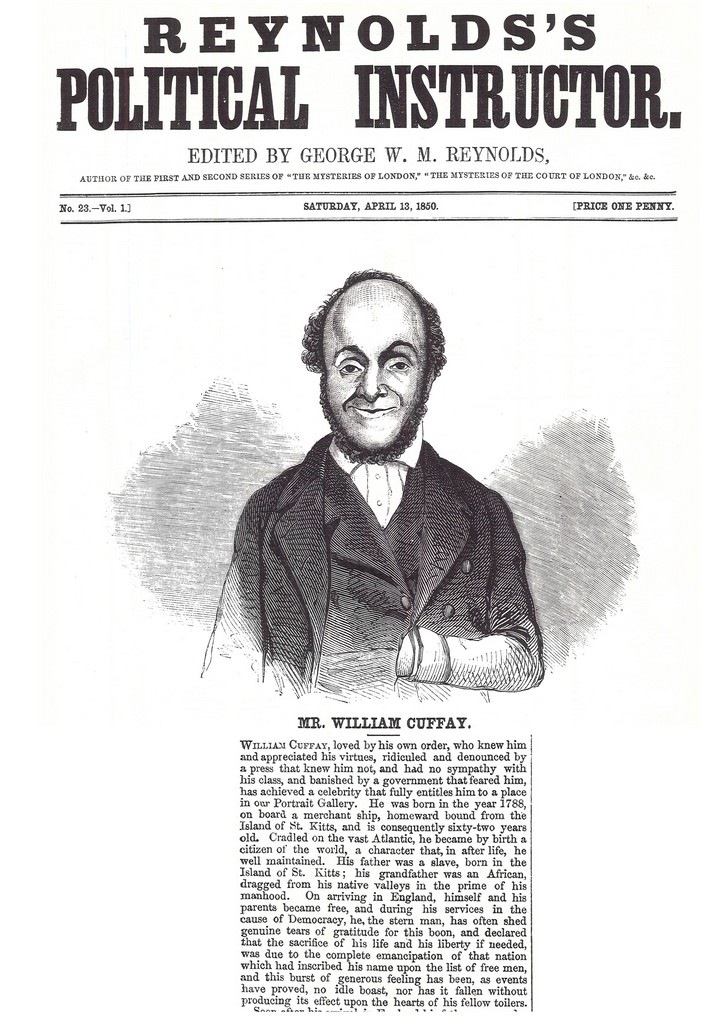

He was mixed race

His Dad, Chatham Cuffay, was a freed slave from St Kitts. Chatham worked as a cook on a British warship, which led him to William’s Mum, an English woman called Juliana Fox. They settled in Chatham, Kent, and William was born there in 1788.

-

He was disabled

William was born with deformities in his spine and legs and as a grown man he was just 4’11”. But his diminutive stature didn’t stop him from later becoming a leader of the Chartists, the first mass political movement of the British working class (more on that later).

-

He was a tailor

If William had been born fit and strong, he probably would have followed his Dad into the Navy. But that wasn’t an option, so he took on a tailoring apprenticeship and in his late teens became a travelling tailor. By 1819 he had settled in Soho, London. By 1834, he was unemployed. He had gone on strike with his fellow tailors, demanding better hours and better pay. The strike collapsed and William was blacklisted from work for refusing to sign an agreement promising not to join a trade union.

-

He got into politics in a big way

And he was good at it – he was described as: “a fluent and effective speaker…always popular with the working classes.” Around 1839, he set up the Metropolitan Tailors’ Charters Association and joined the London Chartists, a party fighting for political rights for working people. Just one in seven men had the vote at this time (and no women, of course). The Chartists demanded that every man over 21 should have the vote. By 1848 William was the leader of the Chartists and TheTimes snootily referred to, “the black man and his party”.

-

He was arrested at home and put on trial in August 1848

The ‘Orange Tree Plot’ was named after the pub where William and other Chartist leaders met. On the weak evidence of police spies, William was found guilty of plotting an uprising against the Queen. In court, he gave a long, dignified speech, saying: “I have been taunted by the press, and it has tried to smother me with ridicule, and it has done everything in its power to crush me … I crave no pity … The press has strongly excited the middle class against me; therefore I did not expect anything else except the verdict of guilty …”

-

He was sentenced to transportation to Tasmania, Australia

Although he was now 60, William survived the long, hard journey on the prison ship Adelaide and arrived in Tasmania in November 1849. His wife Mary joined him in 1853, her ticket paid for by political friends back in London.

-

He never gave up

William was pardoned in 1856 but he and Mary decided to stay in Australia. He worked as a tailor again and got back into politics. As well as campaigning against transportation, he played a big role in persuading the authorities to change tough laws against servants. In October 1869 he was too frail to work and he took refuge at the Brickfields Invalid Depot, where he died in July 1870 at the age of 82. His grave was marked, “in case friendly sympathisers should hereafter desire to place a memorial stone on the spot”.